“Beware the Ides of March.” – Shakespeare, Julius Caesar

March 15, 2023 at 4:52AM Fizzgig was struck by lightning. Fizzgig is a Lagoon 450F with a 75’ air draft.

Chapter One: The Strike or “Crazy Harry Plays With Electricity”

Ryan and I left George Town a day earlier, expecting bad weather coming our way and looking for a safe place away from the busy Elizabeth Harbour, where over 400 boats were anchored. Our destination was Thompson Bay in Long Island, and the sail was amazing. We had a great combination of wind speed and direction that pushed us smoothly out of the harbor and straight to Thompson Bay. These moments, where everything works together nicely, make the difficulties of cruising worth it. When we got there, we anchored, readying ourselves for the strong weather forecasted.

The wind was blowing hard and woke us early on the 15th, before it was light outside. Ryan, always one to take action, picked up his phone and checked the Lightning Pro App to see the storm coming our way. He knows I liked to monitor wind speeds during these situations, so he went to the salon to turn on the navigation equipment and chart plotter. I chose to remain in bed, thankful for his efforts from a distance.

As I heard the beep of from the MFD signifying it was booting up, there was a boom that reverberated through the hull. The boat went dark as Ryan declared, “Oh shit!,” and then repeatedly yelled, “Are you okay?! Are you okay?!”

The lights flickered back on as I peeled Rover off the ceiling and replied, “I am getting the dog off of me!” Once Rover was moved, I ran upstairs to be greeted by smoke filling the salon and the scream of the smoke detectors.

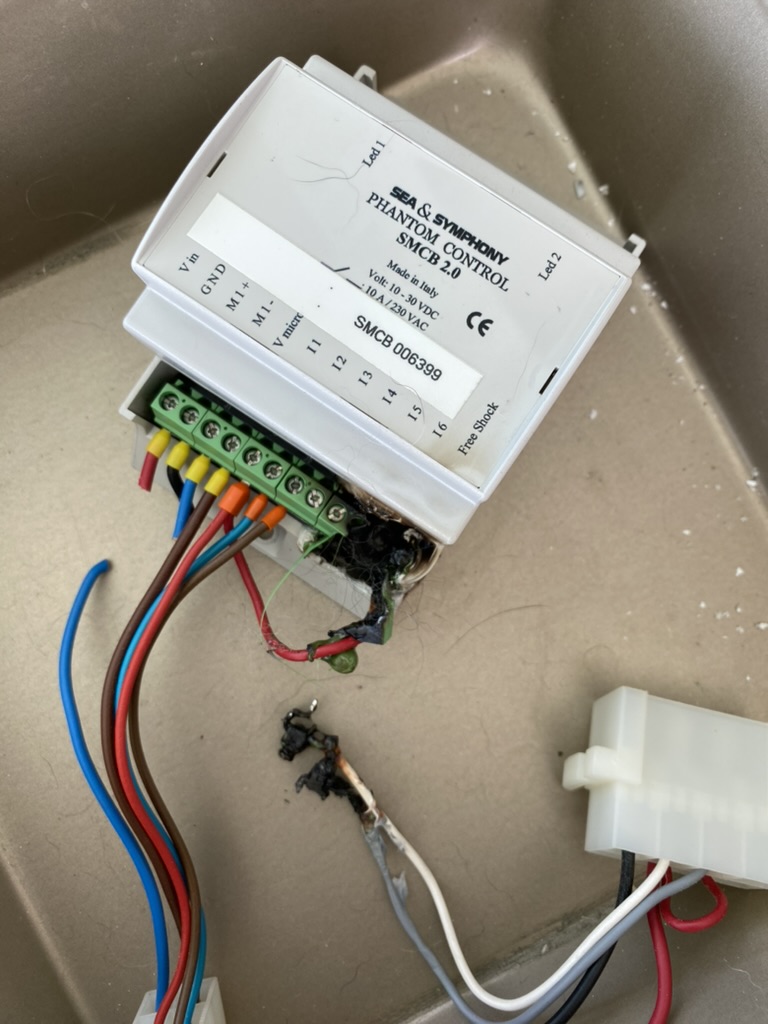

Ryan quickly determined the source of the smoke. The control board for our television lift was on fire. He grabbed the component from the electrical cabinet and moved it outside to extinguish the fire. We opened the hatches to get rid of the smoke and start to evaluate the damage.

We have placed several Wyze cameras in different spots around the salon, monitoring things happening outside. They are good at recording movement. One of the cameras, aimed at the bows, captured the lightning strike on video as it discharged down the forestay to the anchor chain. The timestamp on the video, shows the strike occurred at exactly 4:48:05 AM.

It did not take long to realize there were more systems that did not function than did. We had some interior lighting, refrigeration was still working, and the electric heads were operational. We had no navigation systems; our VHF, radar, chart plotters, depth sounder, wind sensor and navigation lights were no longer functioning. Our engines are all mechanical with no onboard electronic throttles or shifters, so our boat is equipped with devices that remotely control these mechanical systems. These remote controls were no longer working. We could start our engines but not shift into gear or throttle up. Most of our 12V systems were still on, our 220V inverter/charger was no longer functioning while our 120V inverter worked like a champ! We spent the morning and early afternoon attempting to replace fuses and see if there was anything we could jury-rig back to life.

By mid-afternoon we had a few systems coaxed into limited function. One multifunction display (MFD) flickered, reminiscent of a channel with poor reception. Ryan managed to bypass the 220v inverter and get the generator started so we could test 220v systems. Our attempts to test other systems brought mixed results and function.

The water maker powered on and made water but refused to shut off properly, while the dishwasher protested its workload by flooding the galley. On the bright side, the induction cooktop powered up without issue, and the ice maker continued its duty without complaint. When the KVH broadband head unit displayed only cryptic white rectangles instead of the expected status messages. It was clear we had exhausted our troubleshooting options.

With a sense of resignation, we conceded it was time to reach out to our insurance company for assistance.

Chapter Two: First Contact or “Hope Your Insurance is Paid, Frog”

This was our third year under our current policy, but our first year with a new agency after our policy got transferred. Prior to this, our only interaction with this insurance agent was the yearly renewal, which always seemed to require a bit of nudging to get done on time. When we reached out to the new agency for the first time, hoping to file a claim, we were given a phone number that turned out to be entirely incorrect—adding an extra layer of frustration to our already stressful situation. After spending over an hour hunting down the correct contact information, we finally managed to get through to someone who took our details and assured us that we’d hear back the next day. With the clock striking 5 PM, we decided to call it a day.

The next morning, we received our first call from the insurance adjuster, the person behind the scenes who handles payments and steers the direction of the claim. We walked her through our situation, detailing the malfunctioning systems and our current location. Without hesitation, she recommended towing the boat back to Florida and informed us that a surveyor would soon be in touch to arrange the logistics.

I answered the call from the surveyor. He asked what was wrong with the vessel. I began the long list of items that were not operational and was interrupted with a gruff, “Are your sails broken? Why don’t you sail the boat back?” I reiterated that we had no throttle controls so we would eventually need the assistance of a tow boat. I also advised we had people on standby who would fly parts to us to get throttle controls and basic systems working to get back to the US. I was interrupted a second time with the surveyor’s reply, “I guess your boat really isn’t seaworthy and if something were to happen we would be responsible so we will arrange a tow.”

When asked about repair options, we ruled out the two major catamaran yards in South Florida. Instead, the surveyor pointed us towards a yard in West Palm Beach. He assured us that the tow boat would get in touch soon and promised to stay in contact once we reached our destination. We let out a sigh of relief, feeling reassured that everything would be taken care of.

Chapter Three: The Tow or “Send someone to fetch us, were in Sasketchewan!”

That evening, the tow captain got in touch and informed us he anticipated a two-day wait due to the lingering front. Two days later, Roston McGregor of Valiant Marine Salvage arrived. We secured Fizzgig to the tug using a hip tie method, while the Roston skillfully maneuvered both vessels which allowed us to hoist our 105-pound Mantus anchor and 150 feet of 1/2” chain without the assistance of our engines and unworkable windlass.

The tow itself turned out to be the most pleasant part of this whole ordeal. Guided by the Bahamian tug boat, the journey was orchestrated with utmost professionalism, prioritizing safety for all people and the vessel. Navigating through various cuts and a stopover in Nassau due to weather required us to take the helm occasionally, but for the most part, our responsibility was simple: keep an eye on the tow line and make sure we could see the yellow tow light. It took a total of three days spread across eight to reach the West Palm Beach inlet.

On Sunday, March 26, just outside the inlet, our Bahamian tug passed us to a US Sea Tow boat that guided us into Lake Worth. With no further instructions from the surveyor, Sea Tow helped us find a suitable spot to drop anchor indefinitely. We informed both the surveyor and adjuster of our arrival in West Palm Beach and requested a callback during business hours. That night was our final chance to rest with the comforting belief that we were in good hands.

Chapter Four: Month One or “It is hard to soar with Eagles when you work with turkeys.”

In the morning, the surveyor called. His first question: “Where are you docked?” We informed him that we were anchored. To our surprise, he instructed us to contact him once we were docked and had received an estimate from someone. Until then, we had assumed he would be managing the repair process, but it seemed we were mistaken. Instead, he provided us with the name of a boatyard and a marine electrician, offering us some semblance of guidance in this unexpected turn of events.

In the following days, we spent hours on end making call after call. Most vendors and marinas left our messages unanswered. The ones that did respond, were either fully booked for months ahead or simply lacked the space we desperately needed. “Try us again in June, maybe we’ll have something then,” became an all-too-common refrain. Dock space, even just for a brief meeting with the surveyor, was proving elusive, despite his insistence on a dockside rendezvous.

After a week of daily communication between the surveyor and the adjuster, we finally managed to persuade the surveyor to conduct his initial inspection of Fizzgig while at anchor. The inspection itself was brief, lasting less than an hour, with just a few snapshots taken for documentation. We made efforts to showcase the non-operational systems but encountered some resistance. We found ourselves in a back-and-forth exchange, having to convince him our KVH Internet service plan was still active and functioning prior to the strike, while he remained adamant that aluminum couldn’t conduct electricity. With each passing moment, our faith in the process began to wane.

Chapter Five: Leaving Florida or “Movin’ right along…”

One month post-strike and we found ourselves still anchored in Lake Worth without any headway being made towards getting Fizzgig her needed electrical repairs. The spring thunderstorms were started to increase, the humidity was rising and the crankiness level was getting high. None of the vendors we contacted who bothered to return our phone calls, were willing to come to the anchored boat and there was not any slip space available for months. We started looking at options outside of Florida.

After it was explained it was up to us to arrange for repair estimates and repairs, Ryan sent our video of the strike to Steve Wallace at Zimmerman Marine. We were looking for his opinion on a yard in West Palm Beach. We received an almost immediate response. Not only was our question answered but we received multiple messages from various Zimmerman employees with offers of help. They were the only yard we contacted who showed any concern. (Ryan would like to add what I really said was, “Zimmerman is the only yard who gives a f*@k! We are outta here.”)

With repair options in Florida dwindling, we urged the insurance company to greenlight temporary fixes to our throttle control system, enabling us to venture north for more timely repairs. Finally, on April 5th, we received the go-ahead to set sail for Zimmerman Marine in Charleston, SC. The conditions for our journey were clear: we needed functional throttle controls, a basic autopilot, and a handheld GPS to navigate safely.

Fortunately, we had already started the process of gathering parts to make a transit to Charleston possible. This involved numerous trips to West Marine and expedited shipping for UltraFlex actuators from multiple suppliers. In a stroke of luck, we managed to secure the last four in-stock actuators left in the entire US, albeit from three different vendors. By April 13th, we had successfully installed the working throttle controls and a basic autopilot system. We already had a handheld GPS, a handheld VHF radio, and our iPad for navigation assistance, along with temporary navigation lights. With everything in place, we informed the insurance company of our departure plans for the morning of the 14th, readying ourselves for the roughly 350-nautical-mile journey northward.

On the morning of the 14th, we started the engines and Ryan raised the anchor by hand for the last time. After fueling up at the West Palm Beach Fuel Barge, we headed out of the inlet. Unsure of the lightning strike’s effect on our rigging, we played it safe and decided to motor all the way to Charleston, opting not to raise the sails.

The following forty-four hours passed smoothly as we cruised northward, riding the currents of the Gulf Stream. On the second day, we were joined by the largest pod of dolphins we’d ever seen in the Atlantic, adding a touch of excitement to our journey. At 6 AM on Sunday, April 16th, we reached Charleston Harbor Marina just as the sun was rising. After securing our dock lines, a sudden squall rolled in with high winds and rain. It would be weeks before we’d see another chance to make the same passage.

Chapter Six: The Process or “I once waited a whole year for September.”

Early the next morning, we were greeted by the Zimmerman crew who began the process of determining what was damaged and where to begin the lengthy repair process. The surveyor told us to start sending him estimates as soon as possible for approval. The lack of direct communication between the boatyard and the surveyor caught us off guard, leaving us unexpectedly positioned as intermediaries in the process.

Amidst the many lightning repair horror stories shared with us, one recurring theme stood out: insurance companies refusing to pay. These cautionary tales came in many forms but often culminated in denials or partial denials of coverage. For many boat owners, this meant dipping into their own pockets or engaging in protracted legal battles with their insurers. The stark reality was that if we greenlit repairs that the insurance company later deemed unnecessary or uncovered, the financial burden would fall squarely on our shoulders.

And so began the repetitive cycle we found ourselves stuck in.

- Obtain an estimate from the boatyard or part vendor.

- Email the estimate to the insurance surveyor.

- Wait anxiously for two to four weeks for the surveyor’s approval.

- Inform the boatyard that the work has been approved.

- Wait another three to four weeks to receive payment for the completed work.

- Repeat steps 1-5; apply alcohol as needed

The process kicked off with the replacement of our isolation transformers, a crucial step to restore our ability to receive shore power. With shore power restored, we embarked on testing and replacing the upstream components that had been affected by the electrical surge. However, the challenge lay in identifying and replacing components that were dependent on others, prolonging steps one through five for months on end. In the midst of awaiting estimates, approvals, and the completion of work, there was a lot of waiting.

Chapter Seven: Caroline Escapes with the Dog or “You can’t live with ‘em. You can’t live without ‘em”

During the wait for the second estimate, Rover and I left Fizzgig behind and headed for Arizona and California. With sporadic work happening onboard, Fizzgig was far from a comfortable living space for Rover. Those familiar with Rover know he is extremely protective of his home and humans. He has a low tolerance for strangers occupying his home. I called my parents and asked if they could pick Rover and I up. They drove their new motorhome from Tucson to Charleston to retrieve us and took us to Tucson.

Ryan remained in Charleston for the first month. He joined me in California and Arizona in June and returned to Charleston in August. In September, Rover and I returned to Charleston. It was good to have a long break from the boat but I needed to go back.

Chapter Eight: Insurance Jargon or “…all the contracts.”

In the initial stages, vendors frequently inquired about our insurance provider. Upon learning who it was, they visibly relaxed and assured us that we shouldn’t encounter any obstacles. This was good to hear. We were on our third year with the same insurance company. While our policy might not have been the cheapest, it offered excellent coverage with no depreciation. This experience underscored the importance of thoroughly understanding one’s insurance policy and the terms outlined in the contract.

The value of a zero depreciation policy becomes increasingly evident as your electronics age. In our situation, several of our key electronics, including navigation systems and the watermaker, were acquired and installed back in 2015 when the vessel was first commissioned. To complicate matters, the specific makes and models of our MFD, autopilot, and radar had since been discontinued. Having a policy with zero depreciation meant that we could replace this equipment with the latest models without worrying about the decreased value of our older electronics.

I’ve come across policies with depreciation schedules that would have left us covering up to 90% of the cost of new equipment—a substantial financial burden that underscores the importance of opting for a zero depreciation policy, especially for older electronics.

The only item the insurance company denied was the replacement of our standing rigging. Our mast had to come down in order to inspect the masthead, rigging and replace all of the cables for the equipment on the masthead. The rigger who performed the inspection told us this would be replaced because there is no way of knowing the extent of any damaged to metal. The report we received made no mention of lightning and focused on the “normal wear and tear” items for rigging that is eight years old. Two months passed between the rigging being removed and apathetically placed on the ground, us getting the report and the insurance company saying no. We decided to go ahead and replace the rigging ourselves. We paid for the materials; the insurance company had already paid for the labor.

The final piece of the puzzle was the AC/DC electrical panel, a component that required a special order. Its installation marked the culmination of repairs, a milestone reached at the tail end of November.

Chapter Nine: The Escape or “The world’s most dangerous frog, has escaped…”

Back in April, the yard manager in Charleston had confidently declared that repairs would wrap up by the Fourth of July. I couldn’t help but chuckle to myself at his optimism. As any seasoned boat owner knows, taking a boatyard’s time estimate at face value is akin to tempting fate. A good rule of thumb: whatever they tell you, multiply it by three. (Estimate x 3 ≈ reality) In our case, the math worked.

On November 30th, exactly two hundred and sixty days after the morning we were struck, we set sail from Charleston on an overnight journey to Hilton Head. It served as the perfect shakedown cruise—a balance between testing all our systems and staying within reach of Charleston in case of any needed repairs. Fortunately, the trip went off without a hitch.

Epilogue or “Life’s like a movie, write your own ending. Keep believing, keep pretending.”

Since then, we’ve retraced our steps back to Thompson Bay and even crossed over the very spot where we were struck. Despite the passage of time, lightning storms continue to cast their shadow over us. Just this morning, as we find ourselves anchored in Hatchet Bay, Eleuthera, Bahamas, another storm rolled in. Ryan transforms our cabin into a makeshift cave while I turn on the TV for a distraction as the storms rage outside. Lightning, with its unpredictable nature, feels like black magic—always a looming risk when on the water in lightning-prone areas. Yet, in the end, abstinence remains the only foolproof way to avoid its wrath entirely.

While Fizzgig has been repaired, the impact of these events will follow us for quite a while. The insurance company who covered us for this loss sent us a letter of non-renewal before the claim was processed. In retrospect, the adjuster made an error in not declaring Fizzgig a constructive total loss. In boat insurance terms this means the cost of repairs plus the salvage value of the vessel exceeds the agreed hull value of the vessel. Our current insurance agent advised, although there is no fault with this loss, we will be in the penalty box for three to five years for this loss. Our insurance rate doubled in cost and comes with more restrictions than our previous policy.

This experience, albeit challenging, has yielded some silver linings. What started as an unfortunate event, quickly transformed into an opportunity for renewal aboard Fizzgig. In the realm of electronics and rigging, Fizzgig boasts a complete overhaul, a testament to turning adversity into advancement.

Beyond the tangible upgrades, it’s the unwavering support of our loved ones that truly shines. When we found ourselves stranded, it was the generosity of friends and family that kept us going. My parents embarked on a cross-country journey to rescue both me and Rover, graciously offering us a home for a significant portion of the summer. During my stint fulfilling civic duty on jury duty, Rick and Melanie extended their hospitality. Fellow sailors Jerda and Jeremy (of SV Blue Catalyst) and Joni and Norbert (of SV It’s Time) stood by in the Bahamas, ready to lend a helping hand in Thompson Bay. Nicole from SV Imagine was poised to fly in with essential parts, exemplifying the solidarity within the sailing community.

The outpouring of support was nothing short of overwhelming.

- All chapter titles in quotes are credited to various Muppets. Most of them are from The Muppet Movie.